Throughout history, humanism has been prevalent in many different forms of art in order to show appreciation and value of human beings. Greek and Roman art creates a central focus on the human experience through the showcase of the human body itself. Through various Greek and Roman art, you are able to visually see the aesthetics and natural beauty shown through sculptures of humans. The marble statue of Kouros, The Greek Slave by Hiriam Powers, and the Statue of Emperor Trebonianus Gallus are all examples of humanism expressed through the visuals of the human body. These artworks encompass the stance of humanism through the appreciation of the human body as something beautiful in and of itself.

The Greek Slave by Hiriam Powers is one of the most well known sculptures by Power that expresses human experience through the visuals of the nude body. In The Greek Slave, we see a fully nude woman enchained in shackles posed in contrapposto. One reason for the stance of contrapposto was to make the woman look more realistic and have a more natural stance that we would see in the real world. This naturalistic representation of the human body shows the focus on human experience and appreciation of the human body. According to Zygmont, Powers himself says that “The Greek Slave is a woman who has been taken from one of the Greek Islands by the Turks in the time of the Greek revolution. Her father and mother, and perhaps all her kindred, have been destroyed by her foes, and she alone preserved as a treasure too valuable to be thrown away” (Zygmont). After being stripped of everything she has, the maiden is left with nothing but a locket and a small cross to show her devotion and faith to God. Through the showcase of the human body and intense anxiety in the woman awaiting her faith, the audience is able to connect with the sculpture and appreciate the sacrifices that this woman has gone through. The human body of The Greek Slave also allows the audience to connect with the sentiments of anti-slavery and visually picture the struggles that the woman in the sculpture has experienced. According to Reverend Orville Dewey, “The Greek Slave is clothed all over with sentiment; sheltered, protected by it from every profane eye. Brocade, cloth of gold, could not be a more complete protection than the vesture of holiness in which she stands” (Zygmont). In other words, the sculpture does not need to be clothed as the protection from God is all the protection she needs. Through the visuals of the human body itself in The Greek Slave, the audience is able to see the beauties in the human body of the woman and create visual images of the struggles and experiences of the slave during her hardships.

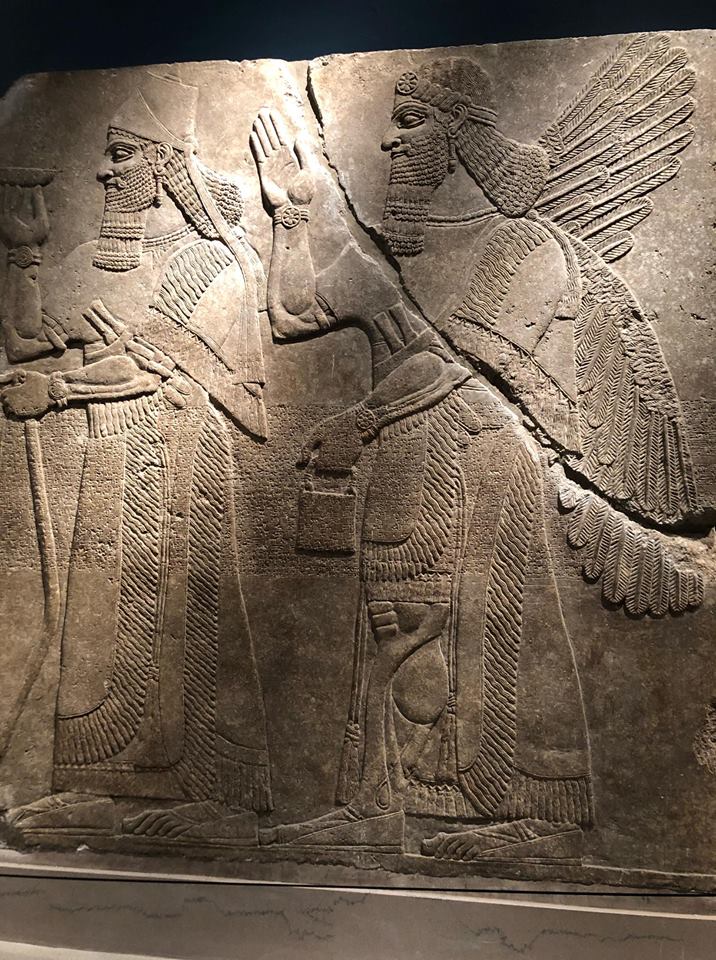

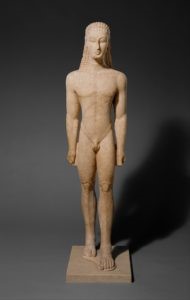

Moving to the Archaic Period, we are introduced to the free standing statue of Kouros. In contrast to The Greek Slave, the Kouros does not offer a realistic representation of the human body. “Frequently employed as grave markers, these sculptural types displayed unabashed nudity, highlighting their complicated hairstyles and abstracted musculature” (Gondek). The sculpture shows a nude male with a very stiff pose having one leg advanced over the other. This wouldn’t be your average every day posture that you would be accustomed to. Nevertheless, the elements of humanism are still evident through the patterns expressed on the human body. According to Richter, “The ideal of the art of the time was evidently not realism as we understand it, but a simplified conception of the human figure, solid harmonious structure, in which essentials were emphasized and generalized into beautiful patterns” (Richter, 52). These patterns that are seen in the neatly arranged hair and symmetrical body of the Kouros show the beauty in this human figure and the purpose of the sculpture to exist through lifetimes. Because the Kouros was meant for funerary purposes, the act of marking gravesites with this statue shows that people valued the meaning behind the statue. According to Harris and Zucker, the Kouros was a “symbol, an ideal of manhood and perfection.” Although different from the realistic and natural representation of the human body, the Kouros still successfully encompasses the elements of humanism through the patterns and the purpose of the statue itself.

The bronze statue of Emperor Trebonianus Gallus is an interesting statue that influenced many people of 3rd century Rome. According to Mattingly, Gallus was appointed the new emperor after the fall of former emperor Trajan Decius. Although people were suspicious of Decius’ death believing Gallus could have aided the enemies at the battle of Abrittus, Gallus did the best he could to protect people from the plague. Gallus ultimately died at the battle of Interamna. In regards to the statue itself, we see a sort of unusual figure displaying very disproportional elements. We are able to see the oversized torso and thighs making his head seem very small in comparison to his upper and lower body. This is very different in comparison to classical ideal figures such as the aesthetics seen in the Doryphoros. According to Marlowe and Harris, there are no archaeological records of this statue. That being said, scholars have come up with assumptions and interpretations of the statue to be so large in size because emperor Gallus was to represent how a soldier-emperor would look in 3rd century Rome. This explains the unnatural non-classical look to the statue because ideal figures in the classical period rose from the ranks of the senate. Scholars’ assumptions as to where the statue was located was at the site of military barracks. “There is little doubt that the site was Mediolanum, the great military centre of ever-growing importance in North Italy” (Mattingly, 37). Through the influence of the statue on soldiers, we are able to see the acceptance of the non classical body and the influences that this statue had on the soldiers that viewed it. They are able to visualize the experiences of the emperor through the visual of his human body.

Greek and Roman art displayed many forms of statues that represented ideas of humanism and appreciation of the human body. Through specific features in these statues, audiences are able to see the beauty in different representations of the human body.

Works Cited

Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Marble statue of a kouros (New York Kouros),” in Smarthistory, December 20, 2015, accessed December 9, 2018, https://smarthistory.org/marble-statue-of-a-kouros-new-york-kouros/.

Dr. Bryan Zygmont, “Hiram Powers, The Greek Slave,” in Smarthistory, January 24, 2018, https://smarthistory.org/hiram-power-greek-slave/.

Gisela M. A. Richter. “The Greek Kouros in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies, vol. 53, 1933, pp. 51–53. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/627245.

Mattingly, Harold. “THE REIGNS OF TREBONIANUS GALLUS AND VOLUSIAN AND OF AEMILIAN.” The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Royal Numismatic Society, vol. 6, no. 1/2, 1946, pp. 36–46. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/42661251.

Dr. Renee M. Gondek, “Introduction to ancient Greek art,” in Smarthistory, August 14, 2016, accessed December 9, 2018, https://smarthistory.org/greek_intro/.